This guest post is by Kim Brown, photographer and naturalist. See more of her great finds at exploringpacnw.net.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

When you think of walking among giants in an ancient emerald rain forest, with lichen-draped branches and carpets of moss, you likely picture the ethereal Hoh Rain Forest on the western slope of the Olympic mountains. But there’s an enchanting old-growth wonderland that may be much closer to you. It is so close, in fact, that you drive there from Seattle in about 80 minutes.

This is the Carbon River Rain Forest in the northwest corner of Mount Rainier National Park, an easy and astonishingly beautiful trail full of damp, green diversity.

Why go now: While much of Mt. Rainier National Park is still under snow in springtime, the Carbon River Road-turned trail is accessible year-round, with well-maintained roads to the trailhead. Rain or shine, this is a close-in, magical place to visit an old growth forest, gather a small bit of history, and immerse yourself in enthralling geomorphology.

Don’t shy away from an old growth forest on a sunny day. One of the more fascinating attributes of old growth forests are the occasional sun patches where toppled trees have left gaping holes in the canopy, letting in sunshine for shrubs to grow, mists to rise and flowers to pop up. And, the forest canopy provides cool shade on warm days, and a sun-shiny riverbank to stop and rest on–if the river isn’t raging.

It was a road, now it’s a trail: The 10.8 mile-long Carbon River Road was severely damaged in 2006 when 18 inches of rain flooded the valley during a 36-hour period. The Park gathered input from experts and the public and ultimately decided the risk of future washouts was too great to justify rebuilding the road where it had washed away. Now, the road is closed to vehicles and has been converted to a trail that leads walkers and even bicyclists through one of the finest old growth forests in the Pacific Northwest.

Hike details: From the Carbon River trailhead, the hike to Ipsut Falls and back is 10.8 miles round-trip on flat terrain. Most of the hike is on the old road, though new trail has been built for the stretches where the road was washed out. About 3.5 miles in is a short spur trail (.2 miles) to view Chenius Falls, worth the side trip. Just before the last stretch of trail to Ipsut Falls is the old Ipsut Creek Campground (5 miles in). This used to be a popular spot for car camping before the road wash-out; now it makes a lovely backcountry camp you can hike or bike in to, but get a backcountry camping permit first. At the start of the trail is an interpretive nature loop that is .3 miles round-trip.

Know before you go: Always check trail conditions before your trip, especially important in spring as winter storms often result in blowdowns and other types of damage to this trail. Check WTA Trip Reports here or the park’s trail updates here.

Hike Highlights and Mossy Tidbits

At the beginning of the trail is an interpretive loop with signs that explain unique characteristics of the old growth forest all around you. Currently the loop is interrupted by a damaged bridge, but go in as far as the bridge; it is worth the visit before starting out on the main hike.

At the beginning of the trail is an interpretive loop with signs that explain unique characteristics of the old growth forest all around you. Currently the loop is interrupted by a damaged bridge, but go in as far as the bridge; it is worth the visit before starting out on the main hike.

From the trailhead, you can see how the swollen river scoured a wide channel, now making the river seem narrow in comparison. The lichen-encrusted, white-trunked young trees in the channel are red alders, the first trees to establish after a flood event. In spring, the catkins on the alders are red, creating a pretty cloud of color hovering above the floor of the river channel.

At about 1.2 miles from the trailhead is a .25-mile long spur trail leading to an old mine entrance (the Carbon River is named after the area’s coal deposits). It’s quite steep and rough in places. The park is in the process of building wood steps on the steepest sections, but for now it’s better to tucker out the children by continuing to walk farther on the main trail.

You’ll notice that many of the trees here are absolutely titanic: Douglas-fir tall enough to pierce the sky, western red cedar, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock – and if you’re observant and lucky (simultaneously), you might see a Pacific yew, an unassuming, scraggly-looking tree usually buried underneath a coat of cat-tail moss. Beneath the moss (it’s OK to peek), the crimson flakes of bark are spectacular.

The living trees in this forest stand tall and have many functions in the ecosystem. They cool the atmosphere and clean pollutants from the air. They provide homes and refuge for birds and small critters. A living tree’s root system provides nutrients for various fungi, and the tree canopy slowly sifts rainwater to the forest floor by dripping it long after the rain has passed by.

It is interesting to know that once these old trees die, they continue to play a critical role in the life cycle of forests and wildlife.

Standing snags can remain for a century or longer, and continue to provide refuge for animals after the tree is dead. When a tree topples, it begins a new “life,” such as providing food and shelter to insects, animals and plants, and providing nutrients as it breaks down.

Bugs burrowing into fallen trees help to break down the wood. You may be interested to know that scientists have studied the role of bug poop in breaking down wood in a dead tree. You may be even more interested to know that bacteria within a bug’s intestine plays a role, too! You probably aren’t interested in the details. Suffice it to say, there are many tiny pieces to the puzzle of how an old growth forest ecosystem has evolved to support the diverse life that thrives there, and some of it even involves bug poop.

As the wood of a dead tree decays and becomes spongy, the water it retains provides moisture to the plants, fungus and animals it hosts, and releases moisture into the atmosphere, helping the forest thrive during the dry summers of the Pacific Northwest. Several hundred years after it falls, the tree ultimately becomes soil.

In spring months you’ll notice mushrooms are popping up here and there, and the birds are beginning to sing. Listen for the impatient-sounding, nasal call of the nuthatch, the happy, rolling trill of the Pacific wren (which have up to 21 song variations), and the eerie, minor-key whistles of the varied thrush. Together, they create an ethereal soundtrack to Northwest old-growth woods.

Don’t forget to look down to the lichen-clad forest floor once in awhile. Rain dripping from these fallen flags of weirdness are one of nature’s ways of dispersing nitrogen-fixing processes throughout the forest. Some types of lichen blown from trees are food for black-tailed deer in winter when other food is buried under snow. Names like “lungwort,” “old-growth specklebelly,” “pimpled kidney” and “frog pelt” seem unappealing, but once you examine just one of these beauties you’ll find yourself crawling around the forest floor quite frequently, looking for more. And if your lucky-streak holds, you’ll hit the jackpot and spot a dog-vomit slime mold!

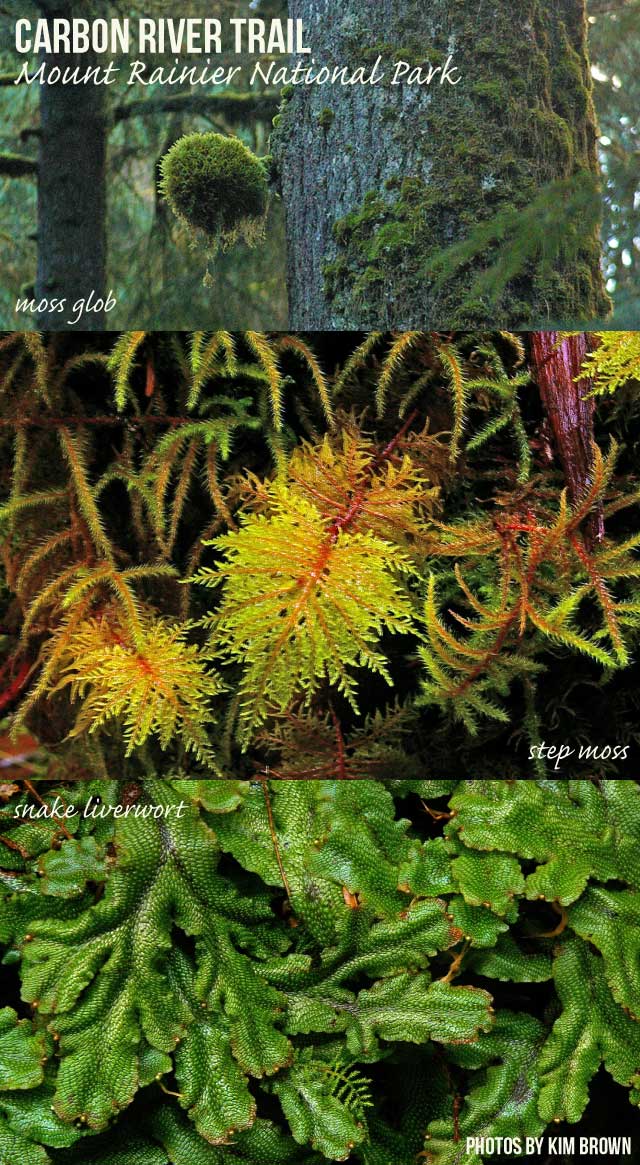

Examine a few square inches of a fallen tree. See the many different kinds of mosses, lichen and liverwort. See the hemlock seedlings, and the variety of fungus, and bugs and slugs.

Mosses, lichens, and liverworts cover logs and rocks, often creating whimsical works of art throughout the forest, as the light plays on a round clump of moss here, an arched branch there or a monster-face log there.

Good to know: While the road is 10.8 miles long, there’s no need to walk the entire length. However, if you can, it is worthy to visit Ipsut Falls and spend the night at the campground there. Remember that bikes are allowed on this closed road, but not on trails beyond the campground at the end.

There is a Ranger Station about a 1/2 mile before the trailhead to the Carbon River Road. Stop in and chat with the ranger to check if there are any trail conditions you should know about, and pick up a small map of the area. An entrance pass is required; pick them up at the Ranger station, or purchase one from the trailhead kiosk ($5 per person over 12, no credit cards accepted). Visit the Mt. Rainier National Park website for more information about visiting this special area.

Safety tip: Always pack these ten essentials on any hike.

Getting There: From Puyallup, take SR 410 for 13 miles to Buckley, then turn right (south) onto SR 165. Proceed to the bridge over the Carbon River Gorge and then bear left to Mount Rainier National Park’s Carbon River entrance.

This guest post is by Kim Brown, a photographer, naturalist and longtime staff-member at Washington Trails Association. See more of her great finds at exploringpacnw.net.

5 Responses

I love your gorgeous moss pictures! This looks like an amazing hike and your descriptions make me want to visit soon:)

Great pics. That snake liverwort looks like something that belongs in Harry Potter world. 🙂

This is close to where we live, will definitely need to check this out more as we’re always looking for a good family hike!

Thank you for the compliments! I love moss – it’s so soothing to the eyes, and soft to the touch; as soon as you walk into a forest covered with moss, you automatically slow down!

And the snake liverwort is among my favorite weird things. The particular clump depicted in my photo was from a log covered with it – it was the largest colony of snake liverwort I have ever seen.

Reminds me of a forest scene in Rivendell from the Lord of the Rings!